Dave Hunt is the vocalist of Anaal Nathrakh and the ex-vocalist of Mistress and Benediction. He has PhD degree in philosophy.

Notes:

I have sent questions to Dave in April 2020, and got the answers in May 2021, so it was more than a year gap – since than, for example „Endarkenment” was released. So, no questions about „Endarkenment” – but Dave speaks about it nonetheless, so there is no loss.

Every external link (except for the one in question number 10, which was added by Dave) and every bolding in text in this interview was added by me – so any mistakes are, of course, my fault.

For those of you who are interested – an article by me with literary and philosophical references in Anaal Nathrakh’s songs that I managed to find.

***

Tomasz Lerka [Alogico Misanthropicus]: Hello, Dave! In one of the interviews you said that you didn’t want to talk about yourself too much, because it was “Anaal Nathrakh interview” – so, I’ve tried to make it more like a “Dave Hunt interview”, with great hope that it will be alright for you.

Dave Hunt [V.I.T.R.I.O.L.]: Hi Tomasz. I’ve tried to answer the questions in the spirit in which they were asked. Which means the whole thing is REALLY long!

1. About a song “When the Lion Devours Both Dragon and Child”, which clearly was inspired by Nietzsche’s “The Three Metamorphoses” from “Thus Spoke Zarathustra” and aphorism $125 from “The Gay Science” (and also parts of the “Book of Job”) – I always wondered, if it was your idea, in which the Lion (second metamorphosis, which stands for opposition) “devours” dragon (which stand for, let’s say, societal norms) and the child (third metamorphosis, which stand for life affirmation and creativity)? And is the idea behind the song that we stop at the metamorphosis of Lion and can’t go further, which leads to situation, in which man becomes full-time nihilist, and negation is his only option, without the possibility of creating or affirming the world? Is hence the use madman’s parable in the chorus? In that way, is the song about being a nihilist (whom failed at trying to be creator) „from inside point of view”?

And also I want to ask you about lyrics of “When the Lion…”, because part of it was published before song comes out on “Eschaton” (2006), namely in the booklet of “When Fire Rains Down From The Sky, Mankind Will Reap As It Has Sown” (2003). Why you’ve done that?

Yes, you’re about right. Basically the original thought behind the metaphor is that the virility and egotism of the lion is needed to clear the path from obedience to self-determination and creativity. Nietzsche envisions a kind of story in which, as people in a society which grew out of judeo-christian values, we eventually find ourselves at a loss, unable to progress because our way forward is barred by this metaphorical dragon. The dragon commands us to do this and that, but it will not permit us any autonomy. More than that, we acquiesce in this, it becomes our accepted state of mind and of being. The dragon isn’t – or isn’t just – some external power or authority, it represents how we approach the world ourselves, on the assumption that there is authority which we cannot oppose, and don’t even want to oppose much of the time. That’s not necessarily a wholly bad thing – the dragon is a source of stability and sureness, especially when we are in this cowed state of being. But it impedes progress and permits no agency or creativity.

I think the dragon metaphor was originally a more-or-less direct reference to Christianity when Nietzsche used it, even though I’m sure he was sensitive to many other ways of interpreting it. But nowadays I think we’d definitely include lots of other factors as well – socioeconomic background, gender, culture, education and so on. These things all shape our world, yet also make it rigid. So then we need that part of us which is represented by the metaphorical lion – our will, our capacity for striking out and declaring ourselves in the world through direct and forceful action. We need the lion to bare its teeth and slay the dragon, thus instantiating and clearing the way for our autonomy, our capacity for self-direction. Only once the lion has done its work and slain the dragon can we move on to a more hopeful, creative phase of being. That’s when we come to embody the part of humanity represented by the child – the part of us capable of wonder and newness and creativity – ultimately, the creativity required to come up with our own values and hence our own world.

But then the twist we put on it is that the process goes wrong, and that all we are left with is the egotism and aggression of the lion, with no creative child coming afterwards. I don’t necessarily mean that we stop at the lion and can’t progress – just that we don’t progress. It’s important for the rage in the song that things could have been different. I think that’s key to us, to Bethlehem, to Marilyn Manson in the 90’s, to Adam Curtis’ documentaries, the horror in a lot of Black Mirror, the satire of early zombie films and so on and so forth – the anger or bitterness or even sardonic glee I see in all of that stuff is partly generated by the fact that things could have been different. Merely reporting that things are a certain way doesn’t generate the rage – it also takes an alternative that was possible but didn’t happen.

I don’t know, maybe I’m overstating it there – the impulse to just fucking burn everything down is compelling too. As if to back that up, I’ve just finished listening to the new Revenge album, and now in the background I’m listening to Profane Order. But that’s just not quite what’s going on with the lion/dragon/child metaphor.

That means I disagree with the way you put things after a point – I don’t exactly see the lion as purely nihilistic and able only to negate. I see the lion more as ego or will – if the dragon is ‘thou shalt’ and the child is ‘I create’, the lion is ‘I will’. That’s not an inherently negative thing – it’s a vital part of existing fully and authentically. The problem is that things get out of proportion – I will becomes the only thing that matters, and that’s what stops us being able to progress – not the lion itself, but the lion’s predomination of the other aspects. The driving force of society becomes only that will – autonomy defended to the death and ruthlessly exercised, but with no worthwhile goal or direction.

Maybe all this is a bit abstract, but at least in part it’s intended as an observation about the world we face right now. I mean obviously the song was written some time ago, but I don’t think it’s any less applicable now. Basically it’s why it doesn’t look like we’re going to be living in a Star Trek Next Gen-style post-capital utopia any time soon. It’s especially present in the ‘strongman’ politics we see so often nowadays – Trump and Bolsonaro are probably the most prominent examples recently, but they’re part of a wider trend. These figures who can attack and dominate, who can conjure up a sense of overthrowing a decrepit and oppressive world order, even though they typically come from some advantageous part of that order themselves. They are all about self-assertion, all will and freedom and agency. But they tend to run out of steam when it comes to actually renewing the world. They can loudly and often simplistically call for the renewal of their favourite parts of the old world, but that’s about it. The only things that strongman leaders seem to be able to reliably create are enemies, and wealth for a tiny, corrupt proportion of society.

And yes, those ideas were going around in my head for some time before we used them in that song, so related lines and ideas may have cropped up in earlier work. Likewise I recently used another spin on the same metaphor as the title of my doctoral thesis. Ideas aren’t finite in time – many things you have to live with at different stages in your life to really understand. And themes can crop up in a person’s thoughts over time just like they recur in modified forms in pieces of music, or in multiple pieces written by one composer. Ok, sometimes you exhaustively lay down a particular idea or feeling in a piece of text or music, and that’s it – you don’t return to it later or dwell on it any further. But not all the time – some ideas stay with you and develop. So if some ideas become recurring themes, that’s fine, it’s just part of a person’s or an entity’s creative identity.

2. “Monstrum in Animo” – if I’m correct, the song is about Socrates, and is based on Nietzsche’s essay “The Problem of Socrates” from “Twilight of the Idols”. In this essay, Nietzsche somehow exposes Socrates as a man who did not love life, and recognized death as a cure for the disease that life was to him. For this reason, the „heroism” or „martyrdom” of his death loses its meaning and value. In this approach, thought of Socrates ceases to be an authentic (at least trustworthy) philosophy. Is this song about authenticity of Socrates, as described above? Is that why you use the words „Have you ever been in love?”, as directed to the Socrates? Since you didn’t love life – or any man – how can you teach a good or moral life? Is that proper reading of the song?

Not quite. The title isn’t meant to signal agreement with the Nietzsche essay, and the song’s not particularly about Socrates, at least not about his character. It was something I was just thinking about more generally, and when I came across the phrase, it seemed to capture things nicely. But yes, the idea referred to was that Socrates apparently saw death almost as a cure for life, summed up in the line where at the end, he called for ‘a cock for Asclepius’. Asclepius was the god of medicine, and it seemed that just as Socrates was drinking the poison which the authorities had ordered he had to use to kill himself, he was calling for a sacrifice to be made to thank Asclepius for curing him – of his life.

I don’t actually share the negative view of Socrates – he may have been a weirdo or a bit of a dick, but he was an inspiration as well, and there’s still very much that’s worthwhile to think about in his legacy, even thousands of years after he died. That’s perfectly compatible with him also being a turning point for the worse in the history of Greek culture, as Nietzsche thought – I don’t know enough to refute that. But reading through some of the essay again, Nietzsche was at his worst there. He was more than capable of writing things in a way which obscured their real meaning, but in the section where ‘…monstrum in animo’ occurs, he’s actually peddling the idea that ugly people are degenerates. That’s something I might do myself – if the ugly person I was referring to was actually a bit of a hero, and my real intention was to highlight the inadequacies of the kind of idiot who would believe it. But Nietzsche’s intent is clearly to attack Socrates, and so I can’t really see how he could have meant it other than at least partially seriously. Or if it was some kind of joke, then it was a very bad one indeed. And even if there is some kind of more subtle gloss you could put on it, I still think Nietzsche let himself down by sinking to that level even just rhetorically.

So no, the song isn’t a musical version of „The Problem of Socrates” – it’s not a rant about how bad Socrates was, or about the triumph of degeneracy over nobility. It’s more of a reflection on how vile people in general can be – we are the ‘monsters in soul’ by virtue of simply being human, or participants in the societies we are, or whatever along those lines. I doubt you need me to give examples of what I have in mind, they’re everywhere. But think of the Milgram experiment as a window on the soul. So the thought isn’t that our own lives are a kind of disease which we each suffer with – it’s misanthropic in a more general sense – there is something sick at the core of humanity, of all people, and all it takes for it to come out is the right circumstances. And the cock for Asclepius is due at our extinction. That’s the cure I’m maniacally raving about in the song, as if we’re all at the point of drinking our own doses of hemlock. The song is kind of similar to „The Lucifer Effect”. But that song is focused more on the reality of the sickness at the core of humanity emerging, while „Monstrum in Animo” is more about the fact that that core exists – different angles on roughly the same thing, I suppose. But that’s fine – some artists release whole albums of just love songs, so we can definitely have a few songs with different perspectives on how awful people are, haha!

The ‘have you ever really been in love?’ section is kind of aimed at how we’ll each feel at our personal equivalent of the point where Socrates drinks his poison. I don’t know, when we’re on our death beds, or just when we seriously and sincerely reflect on our lives. And I don’t mean love in a soppy way – love isn’t just stereotypical, juvenile romantic love. It can be a tempestuous, burning or even damaging experience (for example I consider the Voices album „London” to be a quite beautiful love letter in its own way). Basically love is used just as an example or a metaphor for something genuinely worthwhile. Something that means your life wasn’t wasted. The way that maybe there could have been worthwhile things we did, like loving. And if our lives were measured in those things then perhaps we’d be less monstrous. But although people do value the connections they have with others, for example, that’s not how our culture operates more generally. Hence the sentiment that maybe it’d be no great loss if we were made extinct – is there need for sadness as the cup touches your lips? Perhaps you can answer that yes, you really have been in love, or you have some other equivalently significant thing in your life, and yes, it would be a tragedy for you to drink the hemlock. And perhaps if you can answer yes, that would count against you being among the monsters. But that’s for you to think about and decide for yourself. In the context of the song, I’m basically being a maniac who answers ‘No’ on humanity’s behalf and condemns everyone, haha! That section was actually partly inspired by a quote Neurosis used on „Enemy of the Sun” about 25 years ago – about the distressingly small number of times you’ll actually do things that it seems you have all the time in the world to do. Some people thought they’d sampled Brandon Lee, because he quoted it in a fairly famous interview. But I think it’s from a book that’s 50 years or so older than that.

3. Once in an interview (years ago) you showed big enthusiasm towards de Sade’s book, “Justine”. Is any of your songs inspired by that book (or any other de Sade’s books)? If so, then how did it inspire you? And what do you think about de Sade in general? Do you read Sade’s (and Nietzsche’s) french interpreters, like Bataille and Klossowski? I’m also asking about Bataille because I found titles of your songs on demos by your band Dethroned and it’s just simple association of themes (“Spiritual Eroticism”, “An Agony of Ecstasy”, “The Whine of Sacrifice Outpoured”).

Yes, I enjoyed „Justine”, and found some interesting ideas in it beyond the surface titillation and the lascivious, voyeuristic tone of a lot of the writing (and de Sade’s writing more generally). The ‘might is right’ way some of the abusers defend or justify themselves seemed perhaps to be a bridge between an older understanding of power and a more modern view. I say that because as far as I know, there was certainly nothing new in de Sade’s time about claiming that one’s superior station in life meant that one should be allowed to do as one wanted. And it all raises some interesting ideas about how morality and politics intersect. Tensions about those themes were kind of the whole point of a lot of the events that surrounded de Sade’s life. But I think that implicit in de Sade’s choice to have each of the arousing abusers give a lengthy justification for their actions is the idea that such action must be justified. Yes, characters like that probably enjoy the sound of their own voice and hearing themselves talk about how it’s their right to predate upon others. But even if only on the level of the way we have de Sade, an aristocrat, explaining things for the benefit of his readers – there’s a shift in the locus of power here that I suppose could almost function as a metaphor for the revolution that went on around de Sade during his lifetime. At any rate, how ever you want to interpret de Sade, it clearly wraps up a lot of very Nathrakh-relevant themes – power, degradation, abuse, psychopathy, misanthropy. Not so much the eschatological or pure evil sides of Anaal Nathrakh, but plenty of other relevant themes.

No, I haven’t read any Bataille or Klossowski. I know the name Bataille, but that’s about it. I actually applied to do a continental philosophy course at a university years ago, so I could have ended up studying him. But they wouldn’t let me in, haha! And since then I’ve never got round to that sort of thing very much, just pieces here and there. Actually I had a guy talking to me about Bataille ages ago. And if I remember correctly, he was also the guy who used to go on about Nick Land. And while I’m open to radicalism, I’m not sympathetic to the extreme far-right stuff you find when you go down those rabbit holes. So just by association, the name Bataille makes me cautious.

Thinking about your question made me look up some Nick Land stuff, and it turns out that he used a phrase, Dark Enlightenment, which is quite similar to the title of our new album, „Endarkenment”. But the ideas are quite different. So I suppose I should explain why. The term „endarkenment” is intended as a condemnation of the currently increasing tendency to reject certain things which can be seen as enlightenment values – crucially, of an increased intentional, wilful ignorance and the aggressive rejection of anything which doesn’t conform to an egocentric and solipsistic view of the world. Also, perhaps, the rejection of the idea of knowledge or truth which is expressed in a world where all statements are mere opinion, and all public figures are thought to be liars, and ‘just as bad as one another’ – it seems plausible that the only people who profit from this being a more common view are the worst liars, the worst people.

I’m not an enlightenment evangelist who thinks that any and all ideas wrapped up in the term enlightenment are automatically wonderful. But this turn towards endarkenment is a quite damning indictment of where we as a species are, and where we’re heading. These tendencies are very widespread nowadays – obviously I’m most familiar with public discourse in the UK, and I can think of numerous examples off the top of my head – ‘we’ve had enough of experts’, ‘the only expert that matters is you’, ‘crush the saboteurs’, ‘enemies of the people’ – these are all quotes or headlines from the last few years of public discourse, and in each case they represent an attempt to stifle or crush dissenting, informed opposition. So the idea of endarkenment represents a closing down of critical faculties. And that’s part and parcel of the way societies move towards very dark places.

On the other hand, the dark enlightenment essay, though I haven’t read it in detail, is quite clearly full of projection and appeals to the reader’s sense of wounded exceptionalism. For example very early on, it explicitly says that politics is just about spending more money than your opponent, and that those on the left applaud this, while only the libertarian right opposes it. That’s just not true. And it’s inevitable, Land says, that the ‘libertarian voice’ should be drowned out – which strikes me as an obvious appeal to the way that libertarian right wingers feel as if they’re being silenced by the structure of society itself. When in fact the libertarian right is more in control now than it has been for generations in places like the US (which I think Land is writing for) and the UK, what with Trump’s continuing legacy over there and and a decade of austerity being supplanted by autocratic populism here.

This isn’t the place to go much deeper into all this, and to be fair, I do recognise aspects of what Land talks about when he mentions how massed humans can be fairly awful. But I comprehensively reject much more, from what I can tell. It’s kind of like Mick and I have talked about in the past when it comes to right wing conspiracy-type world views. They seem to start from many different places, and focus on many different things, but for some reason there always seems to be a point at which they start talking about ‘the Jews’! It’s like a joke – oh this guy says this, oh he’s concerned about that… and at what point does he suddenly decide that the Jews are behind it all? I’m not saying Land does this – I am aware there’s a racist current to his ideological stomping ground, but I haven’t read enough of it to know whether he’s actually antisemitic. I’m just saying that in a similar way, as soon as I read more than a couple of sentences, I felt like I knew there was something nasty coming.

And I’m afraid I didn’t write those Dethroned lyrics – when I joined, the band had already existed for a while with another singer, and the songs were already written. So I’m not sure who wrote the Dethroned songs you mention, and I’m afraid I can’t really comment on them. There’s also the fact that we were basically little more than children back then, so they probably weren’t particularly sophisticated, haha! I’m pretty sure that whoever wrote them was into Cradle of Filth and going for that kind of style, but they were before my time so I don’t know.

4. “Paragon Pariah” is about German anarchonihilist philosopher Max Stirner (aka Johann Kaspar Schmidt) and his book “The Ego and Its Own” (“The Unique And Its Property”/”The Individual and His Property”). Is it important thinker for you? Or tragic symbol of anarchistic but unrealistic dream of freedom and expressing yourself in this harsh world? Or maybe both, or maybe something else? Is this song some kind of reflection about his thought and life, and tragic end of his life? About what could happen to you, when you are too extreme in your thoughts? And are they really too extreme in your view?

I like the title ‘anarchonihilist’! Stirner’s book title is tricky to translate, I think, because I think the English words for ownership and property suggest too many things which aren’t quite appropriate. For example if you look up Eigentum on the net, the German Wikipedia definition includes the word ‘Sachherschaft’, which is translated as property, but also has connotations of sovereignty and having power over (i.e. to rule over a thing) or even domination. The English term seems more passive. I don’t know, maybe I’m reading too much into it. But anyway, no, Stirner unfortunately isn’t an important thinker for me – not because there’s nothing interesting in what he wrote, but simply because I don’t know that much about the theoretical side of his work. The reason for drawing on him for that song is more about looking at him as a figure from a distance – his intentions were quite heroic, you might say. But the result of his heroic struggle for self-realisation/self-actualisation/self-determination (surely some of the most heroic things one can struggle for) was ridicule and intellectual ostracism, or at least that’s what I took from what I read about it at the time.

Looking at some of that stuff again now, I can see the links to existentialism, but I think either I’m failing to grasp some of the other stuff, or it’s rubbish. For example he talks contemptuously about anything which goes against pure self-regard – so law, society, love and so on – and how they’re illusory, how the authentic individual seems through them as phantoms. First of all, that sounds like an kind of abstract agent which is radically different from what I understand normally situated human agents to be – at the very least it’s a bit psychopathic. And second, ok, then what happens to the individual’s self-sovereignty when they break laws or behavioural norms? It is diminished or removed, in a physical sense at least, because they end up censured or even incarcerated by other people. And whether or not the individual can then see their incarceration as meaningless, or view those who imprison them as dupes or slaves to fake imperatives, the individual is still in prison!

I get the idea about there being a radical sense of freedom and the self-directed determination of values and so on – that’s basic nihilism, and the precursor to other things, among which would be Nietzsche’s Übermensch, for example. But in the real world of other people and the practical issues their existence presence raises, even the entirely self-interested agent must accept certain constraints on their conduct – precisely out of self-interest, rather than in spite of it. I’m thinking of Gauthier as a clear example – I don’t actually agree with Gauthier in detail, but he famously talks about how agents can cooperate to get more stuff – whatever that stuff is – than they could get if they didn’t cooperate. So maybe farmers can work together and grow more crops than they could if they didn’t work together or something like that. But if they fuck each other over, they lose the extra ‘cooperation dividend’. So if the farmers are entirely self-interested, then they will work together and not fuck each other over. That’s a constraint on their conduct, but it doesn’t come from some delusion about there being rules or values which aren’t grounded in the farmers themselves – the constraint is entirely in service of the farmers’ self-interest.

That’s just a (much simplified) example, but I think it shows how hopelessly abstract some of Stirner’s concerns were. You’re radically free, and property is just about possession and so on…? Cool, good for you. Try to take my stuff and see what happens when I smack you in the teeth! So by claiming this kind of freedom, have you really said anything new that we haven’t known since we were apes?

Well, yes, you have – at the time Stirner was writing, it was a big deal to suggest and to understand that there was this kind of radical freedom on a theoretical level, regardless of the real world practicalities. It’s an important step to realise that we are actually free from the ‘cosmic’ level of normativity which was assumed or implicit in a lot of earlier thought. And obviously he presaged some important themes in nihilism and existentialism, which means he’s quotable to people like us. And obviously it’s thought-provoking, and arguably very compelling. And if you think of a more uncontroversially significant work like Camus’ „The Stranger”, then Stirner is quite obviously part of the thread that leads to that work. But from today’s perspective, in a ‘how to live your life’ sense, or on a serious philosophical level? Maybe not so much – it took others to drive those themes forward before they became compelling to today’s world, I think. At face value, Stirner’s nihilism seems somewhat immature – I’d have written quotes on my school pencil case with immense passion if I’d been aware of him at the time, I think.

Not that long after Stirner, things took great steps forward, both in the ‘continental’, more literary style and in analytic academic circles – for example, you could argue that metaethical non-cognitivists would soon begin to lay post-nihilist foundations, even if they weren’t actually intending to respond to nihilism. And the really interesting debates between non-cognitivists and nihilists are happening right now, I think. If this were a magazine interview I wouldn’t bother – in fact there’s no way we’d have got this far, haha! But given the idea here, I’ll recommend a recent book – „The End of Morality”, edited by Richard Garner and Richard Joyce. That was an important source in the academic work I finished recently, and it’s the kind of thing I have in mind when I mention current debates with nihilists.

Like I say though, there’s a good chance that I’m failing to grasp something here. And I almost certainly don’t understand enough about the historical movements influenced by nihilism!

5. Regarding anarchism, it is theme that we often come across while listening to Anaal Nathrakh. „On Being a Slave”, beforementioned „Paragon Pariah”, „In Flagrante Delicto„, it is composed into the title „Satanarchrist” – these songs by Anaal Nathrakh I am able to mention, but I think it also sometimes appears on Mistress albums. Do you consider yourself as an anarchist? And what do you think about the state? Just as a relations of power (or power/knowledge, as in Foucault work) or maybe something more?

I not sure that anarchism is behind „On Being a Slave” – that’s actually taken from an ancient insult where a slave owner was accused of having breath that smelled of their slave’s cum. That’s why the chorus of the song continues ‘whose breath smells of the master’s cum’. So the insult is based on certain expectations of asymmetrical power dynamics. The idea I had was to mess with that power relationship and insult/humour by noting that powerful figures at the time I was thinking about the song seemed to want the public to love the taste of their masters’ metaphorical cum, but that this was intended as an insult to the masters as much as anyone else. I mean, the specific thoughts behind it were part of what was going on in the world at that time a few years ago. It was the kind of time when the Panama papers were coming out (google it if you’re not familiar), but at the same time battered women’s refuges were closing because according to the subhuman lizard cunts in charge of the economy there wasn’t enough money to fund them. Those are the examples that were in my mind at the time. But the same themes apply to other times and places and people – I’m sure many people could think of equivalent events and people and places today, and there’ll be new venal, self-regarding cunts tomorrow, next year, in whatever country, and so on.

But on what you were actually asking, I think the theme is less one of overt anarchism and more one of rejection of authority, which leads one to be attracted to anarchism, but not necessarily convinced by it in detail. So beyond a certain sense and some quotes and things, I’m no expert on Proudhon or Kropotkin. Generally I think the state is important and in principle has roles which the alternatives can’t play, or at least are very unlikely to be able to play. But at the same time most of the people who direct the actions of the state in the real world are assholes. And they always will be – they’re people, and people are assholes.

It’s a well-known problem, I think – as the saying goes, modern democracy is the worst form of government imaginable… apart from all of the alternatives which have ever been tried. The best form of government to live under would probably be some socially minimalist form of benign dictatorship, i.e. an institutional structure which makes sure people are safe and healthy and not exploited, but gets the fuck out of the way in most other regards. But, to cut an obviously very long story short, no human or group of humans could ever be that dictator because humans are fundamentally shit. So the pursuit of that kind of minimal-stateism is childishly naïve. Yet for the same reason, it seems that the anarchist ideas I’ve encountered are fundamentally over-optimisitc – they seem to operate on the basis of a faith in people’s fundamental decency which I do not share. As I understand it, anarchists are typically attracted to equality and lack of exploitation and flat hierarchies, that sort of thing – basically they tend not to be Nietzschean libertarians or social Darwinists. Yet without a state to intervene, I think that ‘might is right’ will basically win out, and I don’t think that’s a good thing. And I don’t think that’s what anarchists would want either. Of course, many states fail to stop that happening, and in fact reinforce more-or-less concealed forms of might-is-right as a matter of their structure. But that just means the state isn’t operating in a desirable way, because the people running it are assholes… Which is the same reason I don’t think a state of anarchy would be desirable – people are assholes! Anarchy is fine, so long as you’re a predator, or not subject to predation. But it seems like a good thing if there is something like a state that can protect those who are, or who would be, preyed upon by assholes. States get things wrong, horrifically so sometimes, but isn’t it a good thing at least in theory if there’s something which is empowered to stop psychopaths fucking kids?

Thankfully, within Anaal Nathrakh, this kind of thing doesn’t arise. Anaal Nathrakh is mostly negative – it loathes and it denounces, it is scathing and disgusted and bitter. And that’s a perfectly artistically valid way to be. As people – all of us, not just me and Mick – we have to think further, we eventually have to be in favour of things, even if it’s just being in favour of being left alone to do our own thing. That’s part of why many black metal musicians have had to grow beyond the cartoon-like way they presented themselves originally, or remain anonymous. But Anaal Nathrakh as an entity in itself is free to be pure, I suppose you could say – no solutions, no strategies, just pure, evil, spiteful bile.

6. Do you ever thought about releasing a book with all Anaal Nathrakh lyrics? And in interview with Spinal Tapdance you’ve said “I’ve got loads of stuff that’s never ended up getting used in Anaal Nathrakh so far” – how about presenting also this unused stuff someday in a form of book, or essay, or any other form?

No.

7. Who are your favorite composers and why them? We know about Chopin, but who else?

Yes, Chopin is my favourite, because in his music I hear pure expression. I suppose you could use a phrase like ‘art versus artifice’ – some other classical music can sound like it’s a demonstration of how cleverly it was written. Or it can be a bit rigid. That’s how a lot of Mozart sounds to me, and other than his Requiem (which Mick and I both think is amazing), I don’t tend to like his music. But Chopin’s music doesn’t sound like that – it’s incredibly demanding to play a lot of the time (or at least I think it must be), but it’s supremely expressive. Who else? Hmm. I’m not an expert on classical music at all, but I get a lot out of listening to the stuff I like. I do enjoy some of the Russians – it’s probably not surprising that someone who likes Chopin would like Rachmaninov. His piano concertos are incredible, and his first symphony is compellingly dramatic. And I particularly like the Mravinsky/Leningrad recording of Tchaikovsky’s symphony number 4 because it’s very powerful and invigorating. Also Shostakovich – I stumbled across his second cello concerto when it was played as the opening piece before a Rachmaninov performance I went to see. I hadn’t really listened to any of his music before, but thought that was amazing – the opening in particular is incredibly dark and foreboding. And so I read a bit more about him, especially Mark Wrigglesworth’s notes on his symphonies [Symphonies Nos. 1, 2, & 3; Symphony No. 4; Symphonies Nos. 5, 6, & 10; the links comes from me – TL] and how they fit with his life and times (you can google them), and ended up getting hold of a box set of the symphonies, which is enough music to keep anyone going for a good while. There’s also some classical stuff that’s far more intense and powerful than a lot of people who don’t listen to classical music would expect – Allan Pettersson or Schnittke’s requiem are stunning in their intensity. To put it in terms which metal people might more readily latch on to, Schnittke’s requiem sounds like a more sophisticated version of some of the music on the Bloodborne soundtrack. And it recalls some of the feel of The Omen. It’s superb. Or if you think classical music is weak-sounding, turn up the volume and put on ‘Combat de la mort et de la vie’ – Messiaen’s organ cacophony will fuck you up!

8. There is something in your music that – for the use of this interview – I called “dionysian parts” (for example, to name a few, „Paragon Pariah” or “Forging Towards the Sunset” choruses, second part of „Of Horror, and the Black Shawls”, parts of your screaming in “Submission is for the Weak”, last minute of “The Technogoat”, and essentialy almost every clean vocals and almost every from most vicious screams you did in Anaal Nathrakh), which are particularly engaging, beautiful and just powerful. I see it as pure dionysian immersion. I’m sure you understand what I have in mind. My first question about that: is this something you aim for? I mean, this combination of carefully chosen words (and message), style of clean singing (or most vicious screams done by human being) and music behind it. Is this something you’re searching for in creating music? Does this make you happy or satisfied or fulfilled or happier than usual? Or even… makes world more beautiful place? Second question: is this that “building/releasing of tension thing” you once mentioned in your essay from the series of essays “More of fire than blog” – and are you fully aware of doing that during the process of creation music?

I like the fact that you chose the word „beautiful”. It makes me think of listening to Masonna or seeing Whitehouse performances – absolutely not what people tend to think of when they think of beauty, but nonetheless somehow ecstatic and at their best, suggesting something transcendent. I remember years ago being in Athens for a show with Benediction and making a point of going to sit in the Theatre of Dionysus in the Acropolis. It seemed important to take a moment in that place, which kind of seemed like the source of so much. Certainly the kind of music I’ve been involved with has a very strong Dionysian element – it does have structure and technique and those kinds of things which aren’t so Dionysian, but it’s also all about a engulfing sensation that takes you out of yourself and which if more about feeling and can’t necessarily be easily expressed in words. Music in general is an immersive, emotionally evocative artform, and extreme music doubly so, I think.

It can be satisfying to do music which is especially at that end of the spectrum, yes. I’m not a mystic hippie – I don’t record something and then go ‘oh, a moment of pure expression, how fulfilling’ and start hugging people. So I don’t think happiness is the right way to put it. And there’s a slightly method acting kind of element to the way we record sometimes, so any sense of satisfaction is more in retrospect. But it’s still satisfying once you’ve processed it all and can listen back and hear what was coming out.

The tension/release dynamic is definitely real in music, I think. And it’s present in the contrasts in our music, it’s one of the things that makes our music compelling, at least for the subset of people who find it compelling. But it’s not something to have consciously in mind while making music, I don’t think. Music should be expression, not design. If you’re sensitive to the feel of music when you’re making it, dynamic shifts and contrasts will come naturally. But if you’re actively mindful of putting contrasting or even clashing elements together, I don’t think the end result will flow in a satisfying way. The way we put music together is more like working with clay than with different colours of lego bricks.

9. What gives you more fulfilment – writing philosophical stuff or making music? Or maybe they are two sides of the same coin and are both satisfying in different ways?

Well in the end I suppose they’re both completely separate, and not really separate at all. It’s true that in the academic philosophical work I’ve done, I consciously kept it separate from the musical stuff. I didn’t want it to be a vehicle for the same kind of thing I’d done in music. You do sometimes see that, where people shoehorn other aspects of their lives into everything they do – so in my case it’d be something like trying to write a philosophy thesis on extreme metal music. I don’t like that kind of thing because it just seems self-referential and lazy. If you’re stepping into an area of experience or thought, it seems to me that you should get over yourself and seek to prove yourself on that area’s own terms, not try to drag everything on to your own ego’s home turf. Otherwise it starts be some kind of insecure gimmick – if you have a background in black metal, but you want to put your ego aside and make a serious statement in haute cuisine, don’t wear corpsepaint in the kitchen! So if there’s some academic philosophy work of mine that you can find online (there’s nothing much at the moment, but my thesis will be online eventually when the university sorts it out), don’t expect it to be directly relevant to Anaal Nathrakh or an extension of that kind of thinking in any obvious way. That would seem a bit pathetic to me.

But then at the same time, Anaal Nathrakh and the philosophy stuff I’ve done are kind of outworkings of a similar impulse. When I finished my philosophy thesis, I couldn’t resist a little ‘literary’ flourish, and gave it the title ‘How to be a child, and bid lions and dragons farewell’. It’s a serious piece of work on a philosophical level, and it’s not about Nietzsche or anything else that’s obviously Anaal Nathrakh-related. But it’s still kind of subliminally related. It involves a struggle to come to terms with and fully grasp a form of nihilism, albeit a more peculiar and sophisticated form of nihilism than what typically drives Anaal Nathrakh. And like parts of Anaal Nathrakh, it’s motivated by a sense that reality isn’t what we typically think it is, and that the truth about humanity and society involves unpleasantness and the potential for tyranny in ways we’d rather think it didn’t. So even though I’ve consciously chosen to approach philosophy on its own terms, without dragging my musical baggage into it, it doesn’t take a genius to see how there are what you might think of as shared character traits between the philosophical stuff I’ve done and Anaal Nathrakh. In some senses, despite my childish arrogance in thinking I could keep them separate, my academic and musical work are the cerebral versus the visceral or the Apolline versus the Dionysian aspects of the same fundamental thing.

Perhaps one important distinction between philosophy and music is how continuous they are. I don’t know about other people, but even with academic work I tend to be impulsive and work in creative bursts. I can’t just grind it out all the time. It’s more like you have a thought, a flash of inspiration – in my case, often in the shower, strangely enough – and then you have to spend much, much longer writing it out and figuring out the finer aspects. Some of the rest of the time you can do the more ‘administrative’ side of the work when you need to as opposed to when inspiration strikes. But the important stuff tends to come more in flashes. But even then, philosophy is much more of a ‘day job’ kind of thing than music – musical creative work is even more sporadic and inspiration-based. You can sit down and think about something or read a book or whatever, but worthwhile sparks will happen if and only if they want to. You can’t tease out pure inspiration for music like you can tease out the solution to a problem, even if both are essentially creative activities. So I can get up, have breakfast and so on, and then sit down and make myself concentrate on philosophical work quite well, even if the key flashes of inspiration can’t be forced. Musical stuff just doesn’t work like that – it simply has to be inspiration.

10. You – if I remember correctly – said that Anaal Nathrakh is not a nietzschean (or philosophical) band. I may be wrong, but I think that the spirit of Nietzsche is present on subsequent albums. If you have to write short introduction to Nietzsche by yourself, how you’ll do it? And if you want to do it now, that would be great.

That sounds like something I might have said, yeah. People often want to pigeon hole everything. And Anaal Nathrakh is a band – we make music. So although we’ve touched on good old Friedrich, and although sometimes we’ve talked about philosophical ideas, those things aren’t ‘what we do’, any more than Entombed are an ‘Ayn Rand band’ because they used the line ‘a lie has built unto itself a throne in your head’ on Clandestine or a Marvel band because they went on about wolverines later on. Anaal Nathrakh is a music band – we make music, and that’s what this is all about. We use lyrics and ideas that drawn on lots of things, and which can hopefully be rich or important or whatever, but we don’t give people homework or a reading list. And even if we did, there’d be plenty of things on it other than Nietzsche. Obviously this particular interview is weighted towards that kind of material, because that’s what you wanted to talk about. But it’s not the only thing we do – Mick couldn’t give a toss about most of this philosophy stuff, for example!

Having said that, though, yes, obviously I’ve got some acquaintance with Nietzsche’s work. I’m no expert, but I am aware. And one of the reasons I would reject an unqualified association of Anaal Nathrakh with his writings is because I find much in them, or at least in their less sophisticated interpretations, which is repulsive. Just as the man himself would have despaired at some of the things he would eventually be connected with – for example being idolised by proponents of authoritarian fascism would have made him want to puke, I think. But if I was going to write an introduction to a book about him, I think the thing that I’d want to underline would be how optimistic and generous he was, or at least wanted to be.

He’d probably want to defend his right to be more curmudgeonly than that makes him sound. He was nothing if not confrontational. But it’s a gross oversimplification to think that he was only the aggressive contrarian that his detractors like to claim. Yes, you can find some deeply problematic things in his books, depending on your own perspective. But there’s also things like the joy that amor fati and the Eternal Recurrence have wrapped up in them, or the idea of being an ‘artist of life’, or the aspiration of being only an eternal ‘Ja-sagender’. Even when Nietzsche can seem a little absurd, and at times he can, I think we can find worth in some of his actions and attitudes. There’s something of the Florence Foster-Jenkins about his earlier relationship with Wagner – surely at the time it was a profound lack of self-awareness that meant he could show his own compositions to Richard Wagner with any earnestness, but still he did it. ‘Life without music would be a mistake’.

Was he perfect, or someone I could support unequivocally? Fuck no! But at his best – and I know that means cherry-picking from his work – I think he was toweringly, staggeringly bright, penetrating to the point of revelation, and profoundly inspirational. People still invoke Nietzsche’s name today for all sorts of reasons, many of them grubby or ill-informed. But there are also very good reasons to try to learn about and understand what he had to say, and there are very good reasons why he’s worth engaging with, not just as a historical curiosity but as a serious figure whose insights we have not yet necessarily exhausted. Just as an example, I read this not long ago – https://philpapers.org/archive/SILNAC.pdf – it’s a paper drawing out some of the things we can find in and even learn from Nietzsche now, today. It was also written by one of my viva examiners, so it’s kind of cool that although my work isn’t on that topic, the weird connection or relevance seems to hood true for other people, too.

11. As we all know, Anaal Nathrakh (besides it’s live output) is two man band. But – according to metal-archives.com, in the beginnings there was third member – mysterious Leicia, who played bass. Could you tell more about her (him?)?

No.

12. Once you said that “Ita Mori” was inspired by a painting you find over the internet – could you say, what painting was that? And does the song end so abruptly as a metaphor for dying, which is often so unforeseen and unexpected, so violent and sudden?

I had to check, but yes, it was Frans Hals’ ‘Portrait of a man holding a skull’. I don’t think anyone knows who the guy in the painting is, but he was clearly wealthy. Yet inscribed on the wall behind him is that phrase ‘ita mori’ – to perish thus. The point is that even if you’re rich or powerful, you’ll still end up like the skull in the man’s hand, and that’s exactly how the man in the picture – whoever he was – has now ended up too. Along with Frans Hals, everyone wither of them ever knew, and everything that seemed so incredibly important to all those people at the time.

I don’t think the abrupt ending was intentionally a metaphor, though it certainly functions as one in retrospect, and I think that might have been a subliminal part of why we did it like that. We have certain principles that guide us when putting the finishing touches on songs – most of them wouldn’t make much sense to anyone but us, but this one would – we call it ‘OFF!’ Basically it means don’t fuck around with the end of a song, don’t try to be clever or complicated, just fucking stop! Not that there’s necessarily anything wrong with big endings, it’s just what works for us. Bal Sagoth we are not.

13. In “We Will Fucking Kill You” there are quotes from Emil Cioran and his first book, “On the Heights of Despair”. Are you a big Cioran reader? What do you think about his thought, which is indeed expression of tragic nature of human existence [for polish readers – under the link you’ll find my article „Emil Cioran’s approach to the tragedy of human existence” which was published in „Przegląd Filozoficzny – Nowa Seria” this year – TL]? Does his work inspired you in other songs in Anaal Nathrakh or your philosophical work or any other aspect of life? Do you think – as Nietzsche (in “The Birth of Tragedy” and so on) and Cioran – that by expressing negativity we find some kind of temporary, ephemeral peace of mind or serenity? Also, Cioran said that the idea of suicide could prevent us from committing suicide – is this something you would agree on?

No, I’m no expert on Cioran. I did a show in Romania with Benediction quite a while ago, and a guy there come up to me and knew about Anaal Nathrakh, and suggested that I might enjoy reading his stuff. So I did, and found something very compelling in what I read. But I didn’t study him or read everything I could get my hands on. I wish I had, and hope one day to be able to. But there’s only so much time you have.

14. Could you make a list of most influential books for you, your philosophical work, and bands you are/were in? If you could describe why they were and are important for you, it would be great (I’m aware it could be a lot of work and the list would be long).

That’s a horrible question to try to answer. I’ll list a few things that have had specific relevance, rather than just ‘the best ever’ or whatever. Disclaimers: No order, though the first couple are the most recent. And these are just ones that popped into my head – there’s probably plenty of others I missed off. I can’t necessarily remember the details of all of them, they’re just stuff that’s been important along the way, including long ago.

J. L. Mackie – Ethics

R. Joyce – The Myth of Morality

J. Olson – Moral Error Theory: History, Critique, Defence

Plato – The Last Days of Socrates

Cahoone (ed.) – From Modernism to Post-Modernism

Nick Cave – And The Ass Saw The Angel

H. Selby Jr. – The Demon

M. Tanner – Nietzsche: A Very Short Introduction

J. Bjørneboe – The History of Bestiality trilogy

G. Orwell – 1984

F. Kafka – Die Verwandlung

Tolkien – LOTR

J. Le Carré – the Smiley novels (actually an audiobook made by the BBC called The Complete Smiley)

A baker’s dozen, that’ll do.

15. What are you favourite activities outside band and philosophical work? Gym, reading literature, drinking are things I heard about, but what else?

I’ve played video games pretty much my whole life. I was actually pretty good at them at one time, and I played Quake competitively for a while. I wasn’t great, but not too bad. I remember reading that Trey Azagthoth was a decent Quake player, too, but I never ran into him. So yeah, I still spend quite a lot of time playing games as an escapist kind of thing. I’ve also spent quite a lot of time building up a good stereo, partially because music is so important, partially because I find the gear nerdishly interesting, and partially because I like sound itself as well as music (Mick does too, though he’s not interested in hifi gear. Numerous times we’ve had strange looks because we’re going on about the sound of a train or running off to record a noise we’ve heard). So if you think of something like Leonard Cohen’s ‚You Want It Darker’, I find it fascinating the effect of how tangible it seems when it’s played on good gear. It’s musically compelling too, of course, but just in terms of the sound itself there’s another slightly different compelling quality in how the sound seems to live in front of you.

And recently I’ve been dipping a toe into conceptual art. Mick is what most people would recognise as an actual artist – he has a gift for painting, and so on. Whereas I have no aptitude for that kind of thing whatsoever. But I can ‘think’ art, and I recently discovered that there is a world of people out there revolving around that kind of artistic idea – I happened to hear about Haroon Mirza on the radio, and it also happened that there was a free exhibition of his work in Birmingham, so I went to check it out. It’s not the kind of thing I’d have gone to at all until recently, but it opened my eyes to the possibility of doing that kind of work. And for a while now I’ve been having conversations with and then eventually started doing some work with a guy I know who does some conceptual art stuff.

Probably because of my working class background, I instinctively feel like I have to denounce the conceptual art world and at the same time defend my dabbling in it. And to be fair, I do find it hilarious how pretentious and self-indulgent that whole world is, or at least can seem. Especially from the outside, both artistically and culturally, it can appear a lot like posh tossers stroking their chins in front of a pile of bollocks when they’d be better off going and getting a life or maybe getting laid! But at the same time, working with my mate, the ideas we discuss and try to find ways of articulating are really interesting and quite powerful to us. So whatever the perception of that kind of conceptual art work, I’ve got a lot out of beginning to scratch the surface of that kind of thing, and with any luck working with this friend of mine will lead to exhibiting a piece of work somewhere. As long as it’s authentic, I think you just have to follow what interests you where it leads, rather than be prejudiced about it. Without following inspiration where it leads, we wouldn’t have any extreme metal either. And there’s nothing necessarily contradictory about getting a lot out of experiencing a piece of art, while at the same time thinking the person next to you in the gallery is probably a wanker, haha!

16. Do you ever listen to a band with harsh vocals (in craziest Anaal Nathrakh and Mistress parts, like “The Technogoat”, “Castigation and Betrayal”, “Hold Your Children Close And Praise For Oblivion” and many, many, many others) similar to yours? Honestly, I listened to thousands of bands, and never found anything like that.

Hmm, there are certainly other singers whose unique extremity I enjoy – Joe Horvath from Circle of Dead Children, Dean from Extreme Noise Terror, the chap from Solefald on the Linear Scaffold album, Rainer Landfermann and so on. And others who might not be quite so extreme, but who are very individual – Edgy 59 or Attila or Ghost/Geist. I don’t think many people sound quite like me though – or indeed quite like those people I just mentioned. I can’t speak for anyone else, especially anyone on that little list, but I’m not sure that very many people actually intend to do what I intend to do in the first place. Lots of people in bands just think of the kind of band they’re in, and try to do what you’re supposed to do in that kind of band. Very well in some cases, of course, but nonetheless still the kind of thing that you’re more-or-less supposed to do. Whereas others think differently and do whatever feels right, or just try to express themselves more directly without reference to style. I’m somewhere in between – I do use some idiomatic styles, but I also ignore everything and do whatever feels right. And so the harshest parts you mention aren’t an attempt to ‘sound black metal’ or whatever, they’re just driven by a desire to do something completely harsh. That’s not what a lot of people are aiming to do, and so it’s different than a lot of what you might hear elsewhere, both in intention and in result.

17. Movies. I know you appreciate movies like “Mulholland Drive”, “Dogville”, “Elephant Man” and so on. What are most influential and important movies for you? And why? In what way they influence your music? And maybe any other aspects of your life?

I’ve actually never see The Elephant Man, though I’m aware of it, obviously. I’m not really a film buff, I’m no extreme metal Mark Kermode (if you don’t know him, he’s a UK film critic who’s a bit obsessed with The Exorcist, is a down to earth academic type of guy, and plays music in a band – so you might see a jokey kind of parallel). I’ve really enjoyed some quite ‘serious film’ kind of films like those you mentioned or 13 Assassins or The White Ribbon or whatever. And I think that films can say important things, for example Die Quelle, or be profound or profoundly thought-provoking, like maybe Import/Export. But I’m not experienced enough to be someone whose opinion on films it’s worth paying much attention to, and films have seldom been a big influence. Back when such things were common, probably my favourite DVD purchase was an impulse buy in a supermarket of a box set of Robocop, Commando and Predator. So you really shouldn’t listen to me about films!

It was good working with a film maker to make a video for the title track of Endarkenment not long ago, and one of the things that struck me about it is how I just don’t understand the language of film. I can pick things up in films, I’m sure we all can to some extent. But when it comes to having thoughts on how to film something, I’m lost. I have the conceptual stuff, I can talk productively with a film maker about themes, visual metaphors, that sort of thing. But give me a camera and I’ve got nothing. Just like with ‘normal’ art, I find myself a conceptual artist who can’t hold a pencil. Film’s an art form and a set of sensibilities and talents all of its own.

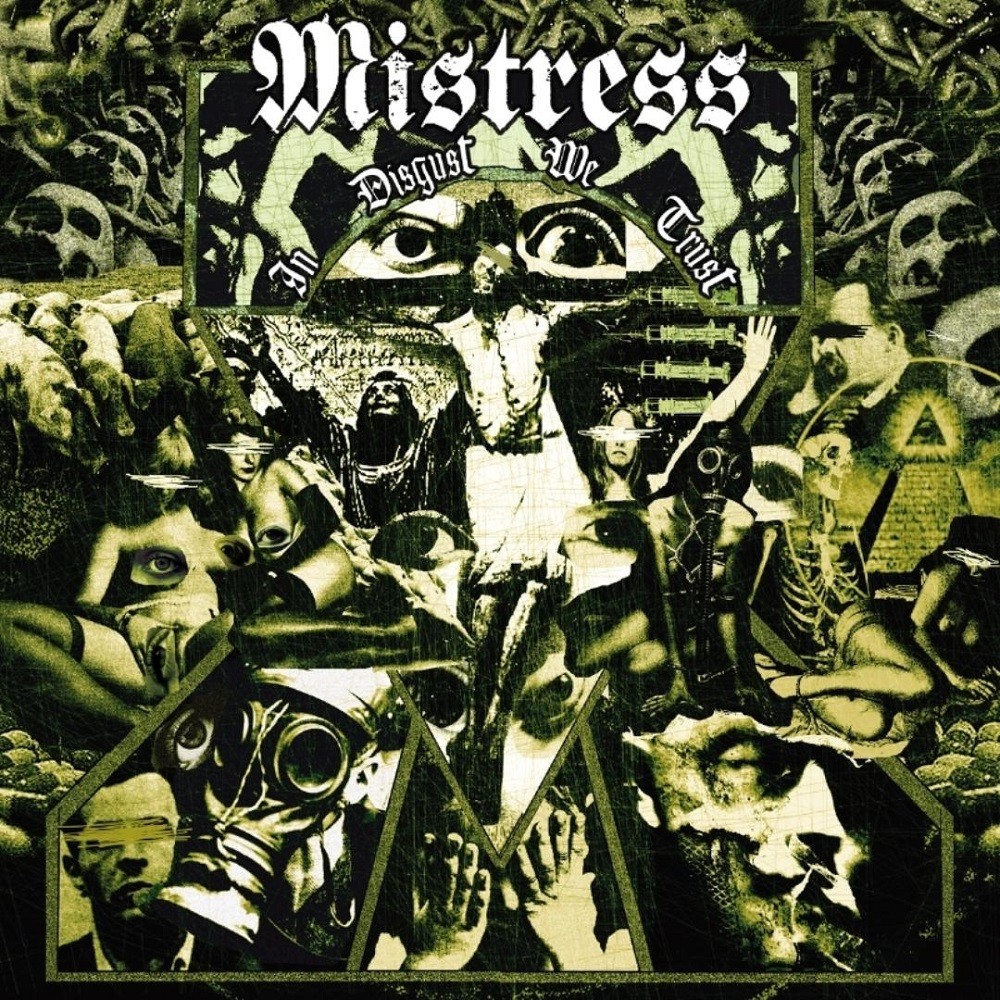

18. Besides Anaal Nathrakh, you also played with Mistress and Benediction. Let’s try to put it this way – if Anaal Nathrakh is somewhat expression of the tragic nature of human existence (or conclusion of tragic nature of existence) in the world, misanthropic, full of despair, pain and madness, Mistress is other side of this coin, probably more “daily practice” of alcoholic, depressed, in some ways ugly, angry individual which even tells God to “go fuck yourself” (“naked and bleeding” but with “no regrets” to destroy his life, instead with laughter). Anaal Nathrakh and Mistress are both the outlet for rage, pain, fear, subversive emotions and ideas et cetera. And, in that way, they are complementary. Is that accurate (but probably too short) description?

And if so, what Benediction was for you? Just pure death metal fun without strings to your individual way of looking at the world and human existence? Or maybe something more?

Yeah, you’re about right in all three cases. I’m glad you picked up on the way Anaal Nathrakh and Mistress relate to one another. It wasn’t particularly the intention to do it that way, everything just came out of doing what felt right. But the way you put it is pretty much how it turned out, and how it feels.

And yes, with Benediction, the band already existed and was fully populated with strong personalities for a long time before I came along. And I only came to it by chance. So in that band, it felt like my part was to slot into that and try to stay true to what it was both internally and in the fans’ eyes. So while that stuff is obviously part of who I am, being in Benediction wasn’t about self-expression in the way that Mistress was or Anaal Nathrakh is. That’s not to de-legitimise my time with Benediction, of course – those guys, especially Daz and Rewy, remain some of my closest and most admired friends. It’s just that the bands were about different things.

But yeah with Mistress and Anaal Nathrakh, I think perhaps you could say that Mistress is what happens to you as a result of Anaal Nathrakh. Anaal Nathrakh is concerned with the big, the deep, the cosmic-level, the human condition kind of stuff, while Mistress is more like living with the human effects and costs of things – be it spending too much time obsessed with that Nathrakh-ish stuff, or just struggling to cope with life in a more every-day way. On one hand there’s wrestling with god and mortality and screaming at the void, and on the other hand there’s piss and cider and razor blades.

19. Once in an interview you said that you are a “militant atheist”. This is interesting for me, because if we take Anaal Nathrakh – in which pain of being in the world is articulated really strong (like I tried to describe it in previous question) – and I fully understand atheist position, but why being “militant”? I mean, if the world is that tragic place, and people find comfort in their religions, and also you know to what conclusions atheism (or lack of God) drives you, why try to take this comfort from them? Doesn’t it increase the amount of suffering in the world, which can’t be cured anyways? Or is it because people should know the sad truth (however you understand this term)? Awareness of this tragic wisdom is better then blissful ignorance? And do you find religion as a source of evil (not necessary all evil, but a part of it)? Of course, we know about many hideous crimes committed by religious people, like pedophilia, and many other unforgivable, terrible things, but shouldn’t we look at religion in these cases more like veil (cover, facade) or excuse for perverted criminal acts than it’s source? I’m not taking any positions here, as “religion defender” or anything, I’m just interested in your view of this topic. And what do you think of the new atheist movement, like Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris etc?

Hmm, how long have you got? Haha! There’s actually not much that’s implied by atheism in motivational terms. There’s nothing to say that atheism is any more motivationally powerful than not believing there’s a teapot orbiting Betelgeuse. So I think any actions or attitudes you have in response to atheism – whether that’s realising you’re an atheist, or if it’s in terms of responding to other people’s atheism – are really a matter of what your other motivations are. What I mean is, let’s say that I was religious, or simply had no feelings one way or another – if I then realise that there is no god, how will I react? I think the answer to that depends on who I am more generally. It’s not the existence or otherwise of a deity that determines the character of my response to becoming an atheist myself.

So for example if I am someone who antecedently values truth, even if that truth is brutal and hard to accept, then I will fight and take an aggressive stance towards coming to believe that there definitely is no god. That truth may be hard won, and I might be quite fierce or inflexible about it. And if I am concerned for the autonomy of others, I will want – maybe even fight for – others to know that truth, too. I will probably be intolerant about others believing what I know to be false. But I may also feel grief for the sense of security I previously had before I realised this difficult truth, and deeply regret that others will also have to cope with this realisation, just as it can seem tragic that children have their innocent fantastical beliefs slowly destroyed as they become adults. If, on the other hand, I started out as someone who was primarily concerned with pragmatism, with how useful and beneficial things are, and who is willing to put up with a bit of vagueness or pantomime, so long as it’s for the best, then I will react differently. I will say things like you just said about it being ok if people believe false things, so long as they’re happy. And there could be many other nuanced ways of responding, of course. But taking these two types of response as examples, the first one is what I would call militant, not the second one.

Frankly nowadays I wouldn’t class myself as militant in that sense – at least, not as militant as I was when I was younger. I still feel my militant hackles rising when I come across William Lane Craig-style theism (google him if you don’t know him – he’s one of the foremost professional Christian apologists), but more generally it feels there are more pressing problems too much of the rest of the time. Similarly, if Christopher Hitchens had been born that much later (30 years or so later, maybe?), I’m not sure he’d have felt as motivated to fight religion today as he was in the 90s and 2000s. He’d have been occupied with other things, like the catastrophic mendacity of world leaders and the rising spectre of fascism in Europe. That’s my guess, anyway. I’m just not sure it seems as important to oppose Christianity as it once did – that doesn’t mean that any of the reasons to do so have changed, it’s just that it’s less of an issue in today’s world.

And in recent years, criticism of religion in the West has become intertwined with race, because public narratives about religion now focus more on Islam, and many people seemingly can’t tell the difference between the demands and dictates of a religion, the individuals who believe in that religion, and the colour of a person’s skin. It’s not 1998 any more. For example, I recently spoke to an otherwise well informed and bright person who recoiled at the name Sam Harris because all he’d really heard about Harris was that he doesn’t like Muslims. Now I suppose it’s possible that Harris doesn’t, but I have seen no evidence whatsoever of that – it’s just that as a critic of religion, speaking out in today’s world, the association gets made whether he’d want it to be or not (and I believe he’s explicitly said that he doesn’t). So the bottom line is, unless you actually do want to make some subliminal point about race – and I certainly don’t – then why bother? When you encounter religious faith, isn’t it easier and possibly wiser, unless someone makes a particularly egregious comment, to just think ‘dickhead’ and move on?

Now of course that opens up troubling new questions, such as those raised by the apparent inversion of the public/private distinction in religion. Many people, including vocal atheists, used to be content with religion being a private commitment and practise, while it remained fair game for sincere debate in public, at least in general terms. Nowadays I think that arguably things have swapped round – more people proclaim and demand indulgence for their religious beliefs in public, but the criticism has to be more private. I suspect you’re more likely now to get no-platformed or attacked for being an outspoken critic of religious bigotry than you are for publicly supporting a religion that condones the murder of homosexuals, as the Abrahamic religions frequently do. Or think of the difference between the avowed religious faith of the two most powerful men in the world over recent years – Obama mentioned religion and occasionally practised it publicly, but this was – or at least felt like – a public manifestation of something notionally private. Even as a cynical atheist, when he ‘spontaneously’ sang Amazing Grace at a public memorial service, there was something compellingly non-stunt-like about it. Whereas Trump shouts about Christian values and poses with bibles all the time, but it’s much harder to believe that that behaviour is the product of any particular private commitments. It doesn’t matter whether either man is actually religious (plausibly, neither is), or whether their religiosity is just for show (probably) or a good thing (almost certainly not). It matters that their difference is symptomatic of a change in perceptions about religious superstition more generally. This is all digressing a bit too much, though.

There are a couple of other reasons for using the term militant – one, to underline the way I am not an agnostic. When some people say they are atheists, they don’t seem to mean it enough, if that makes sense. They mean ‘I don’t believe in God’, but they haven’t thought about it much further than those simple words – they’re basically agnostics who take an extra step, rather than being theoretically hostile to religion in all its forms or anything like that. Whereas I mean there absolutely, definitely is not anything even vaguely resembling a god, and there could never be. And even if there were some super-competent conscious entity, it would be nothing like the kind of Christian god I was raised to take as the default kind of deity. And if there was such a being, I would want to categorically reject its teachings and requirements if they were anything like the religious teachings I’ve come across in content or implication.

Having said that, I find it difficult to approve of the ‘New Atheists’. I’m not an expert on them, but I have read The God Delusion, and have watched quite a few of Hitchens’ debates with theists, for example. Two in particular – the one with him and Stephen Fry against Ann Widdecombe and Archbishop Onayeikan, which was a landslide in favour of the atheists, and the one with William Lane Craig, where I felt that Hitchens comprehensively lost. (As an aside, I wrote a dissertation on divine command theory a few years ago, and listened to a number of WLC debates as research. I even went to see one, against Peter Millican from Oxford university. And I can only think of one of WLC’s debates that I’ve come across where I think he lost – one with Shelley Kagan. Even as someone who passionately disagrees with what he says, I’d be a fool not to admit he’s a masterful debater). But from my limited experience, there seems something almost arrogant about the way the ‘new atheists’ go about things – they sometimes seem to want to replace psychologically totalitarian theism with psychologically totalitarian scientism. There’s an ironic whiff of dogmatism about them generally. And whether it’s true of them personally – and I suspect it’s actually not – there’s an atmosphere around them of being the kind of people who would walk into the St. Vitus cathedral or the Basilique du Sacré-Cœur and just laugh loudly and declare as publicly as possible ‘well this is all just rubbish’. And I can happily say, even as a sometimes snarling atheist, that I don’t find that quality attractive either theoretically or aesthetically. Like I say, I doubt they’re actually like that on a personal level, but I’m talking about what you might call the ideological atmosphere around them.

Obviously that’s a subjective aesthetic judgement, but it reaches into more substantial areas – for example a few years ago I was talking about this kind of thing with someone, and it led into discussing consciousness. The person I was talking to had a very rigidly science-focused view, similar to what you might expect someone like Sam Harris to have. I replied that I didn’t think neuroscience was necessarily the best tool for understanding consciousness, because it leaves out what used to be called qualia – subjective experience. Like how you can describe vision in minute scientific detail – wavelengths of light, lenses, retinas, rods, nerves, neurons and so on. But none of that captures what it’s like to experience seeing the colour red as a sentient human being. The person didn’t seem to want to talk to me any more after that, haha! But I once saw Harris attack theists as those who would argue that ‘science can’t be applied to the most important questions in human life’, and attempt to ridicule that position. But even though I’m completely convinced that religion is complete rubbish, I’m still not convinced that science can capture the quality of subjective experience. And if I think there’s anything at all that science can’t capture, then that puts me in opposition to some of the new atheists as I (possibly wrongly!) understand their position. There’s actually a view of consciousness called panpsychism that sounds like absolute batshit rubbish when you first hear it, but which I suspect might be able to capture some of the naïve worries I have about it all. So I’ve just started reading a recent book about it called Galileo’s Error. Should be interesting…

20. Once you’ve said that „finding God is not on a menu”. In previous question we touched on this topic, but it still interest me – and it is not a complaint in any way – but I think about philosopher (or thinker) as a constant seeker who is never completely sure of his previous answers (at least, with the “big questions”) and constantly tries to undermine them (and for this reason, if he finds any weakness in the previous answer, he changes it on the basis of a new stimulus and adapts it to the new reality). And when you said that you will never believe in God (or be religious), don’t you limit your options? From that point of view, by stating that, you close a path that can be quite fertile in an intellectual way. And we have so many things that we can’t be sure – so why such certainty about God? Of course, one of the answers may be laziness or the convenience of settling in some clear, formulated belief system, but I would never dare to accuse you of it.

Please, do not misunderstood me, I’m not saying that this is your case, but sometimes it happens that our rebellion ceases to be well-thought and becomes a habit, an automatic, sometimes also an angry, rapid response – for example, to the suggestion that God exists. I also understand a different attitude, because sometimes I behave in such a way that I am a believer among atheists and an atheist among believers, simply because people both believe and do not believe for stupid reasons. But the conversation is of course about you – so how do you see these issues?

I disagree with your characterisation of ‘the philosopher’ – this idea of the constant ‘seeker after truth’ who is always spiritually open etc. is not what a philosopher is. It’s what the spiritualism section of a crap bookshop would try to tell you a philosopher is, and that’s a very different thing. Yes, I think the kind of falsificationism you mention is fine – test ideas constantly, and always review and reappraise weaknesses, no matter how uncomfortable it may be to do so. It comes from science, and it’s a good method. That’s all good stuff. But that doesn’t mean that you must never take yourself to know anything for sure. That’s not what scientists do, and there’s no reason why philosophers or anyone else should be so wishy-washy either. Religion at its worst is jealous, violent, despotic, cruel, exclusionary, bigoted, the list goes on. In order to maintain beliefs which are well justified, I do not have to concede that any of those things could ever be good, or could be supported by the best reasons to believe in anything.

Let’s make Godwin’s leap for the sake of illustration – I am not a Nazi, and I will never be one. That’s not because I’m closed-minded and dogmatic, when really I should treat my conclusions on the matter as somehow provisional. I’m completely comfortable with saying that it’s because the values and ideas behind Nazism are just plain wrong. (Philosophy-aware people might realise that there’s something in common with Simon Blackburn in what I’m saying here, though I don’t necessarily agree with him more widely.) I don’t see any reason at all to acknowledge any possibility that new evidence will come to light and show me that I was tragically mistaken, and actually people of certain religions and races should, for reasons intrinsic to their race or whatever, be gassed to death. I am not going to go about my life while maintaining that maybe, just maybe that’s what I’ll come to believe. And even if at my very worst, most angry and bitter times I might think that some people deserve horrible things to happen to them, I will never look at Nazism and think that yes, those people deserve that treatment for those reasons. Well, perhaps I could be forcibly brainwashed or something like that, but you get what I mean – I will never freely come to that conclusion because it contradicts what I take to be knowledge, not just potentially unwarranted belief or opinion.

And in just the same way, there is no reason why I should allow any possibility at all that all of my actions are judged by an invisible supernatural being, whose existence is supported by precisely no evidence whatsoever, who commands me to believe that homosexuals deserve to be tortured with fire for millions of years. Yet in the question, there’s a suggestion that somehow my conclusions about that should be somehow provisional, and I should be willing to reverse them? No, sorry, fuck that. Physicists don’t have to allow the possibility that the entire observable universe could turn into a cauliflower tomorrow afternoon, and I don’t have to pander to the suggestion that people I know who are worthwhile human beings should be damned – whatever that means – because of some rubbish that an ancient bunch of people wrote down, many years after their cult leader had died, because they were so scared that they were secretly a bit gay. Part of the reason I reject religion is the fact that it seems so transparently to be based on all-too-human insecurities.